Night had fallen. A dozen tortoises surrounded us. Almost naively, I asked Francis, the island’s manager, what message Aldabra might want to send to the world. “It would be a cry from the heart,” he said. “I am unique. Protect me.”

This was a day of transition, when one team replaced another. Alexis and his daughter Maluha, both professional divers, along with François, the cameraman, were leaving the Dune Jean-Louis (DJL) camp to return to the scientific base on Picard Island, Aldabra’s main station. Morgane, the stopover coordinator, Marine, head of media, and I were to take their place for four or five days on Grande Terre. The two teams met at the “landing point,” a narrow zone between the mangrove and the jagged karst limestone belt that makes the island so difficult to reach.

“It’s a bit rough as a camp, but Yanick, the cook, is excellent!” called out Alexis as the boats crossed paths. “You’re in for a treat.”

It was nearly noon when we arrived at the camp. Lunch was already ready: rice with tomato sauce, and it was a hit. We then set out to walk east along the shore, where plastic waste was scattered along the coastline. Most of it consisted of jerrycans, hundreds of fishing buoys, and thousands of flip-flops. They came in every size, pattern, and color. We decided to collect them to later send to Ocean Sole, a Kenyan NGO that turns discarded “flip-flopi” sandals into colorful animal sculptures such as turtles, rhinos, giraffes, and hippos, and with whom Plastic Odyssey had already partnered.

As I gathered sandals from the sand, I couldn’t help but wonder about their stories. Who once wore them? Who bought this pink pair, perhaps a father for his daughter? And this one, half-chewed by a fish, how did it end up drifting through the ocean only to wash up on Aldabra? Was it thrown overboard during a storm, or after a shipwreck?

“We only see a tiny fraction of the plastic dumped into the sea,” explained Simon Bernard, expedition leader and founder of Plastic Odyssey. “Most of it dissolves in the water, breaking down into micro- and nanoparticles. Every minute, nineteen tons of plastic waste enter the world’s oceans.”

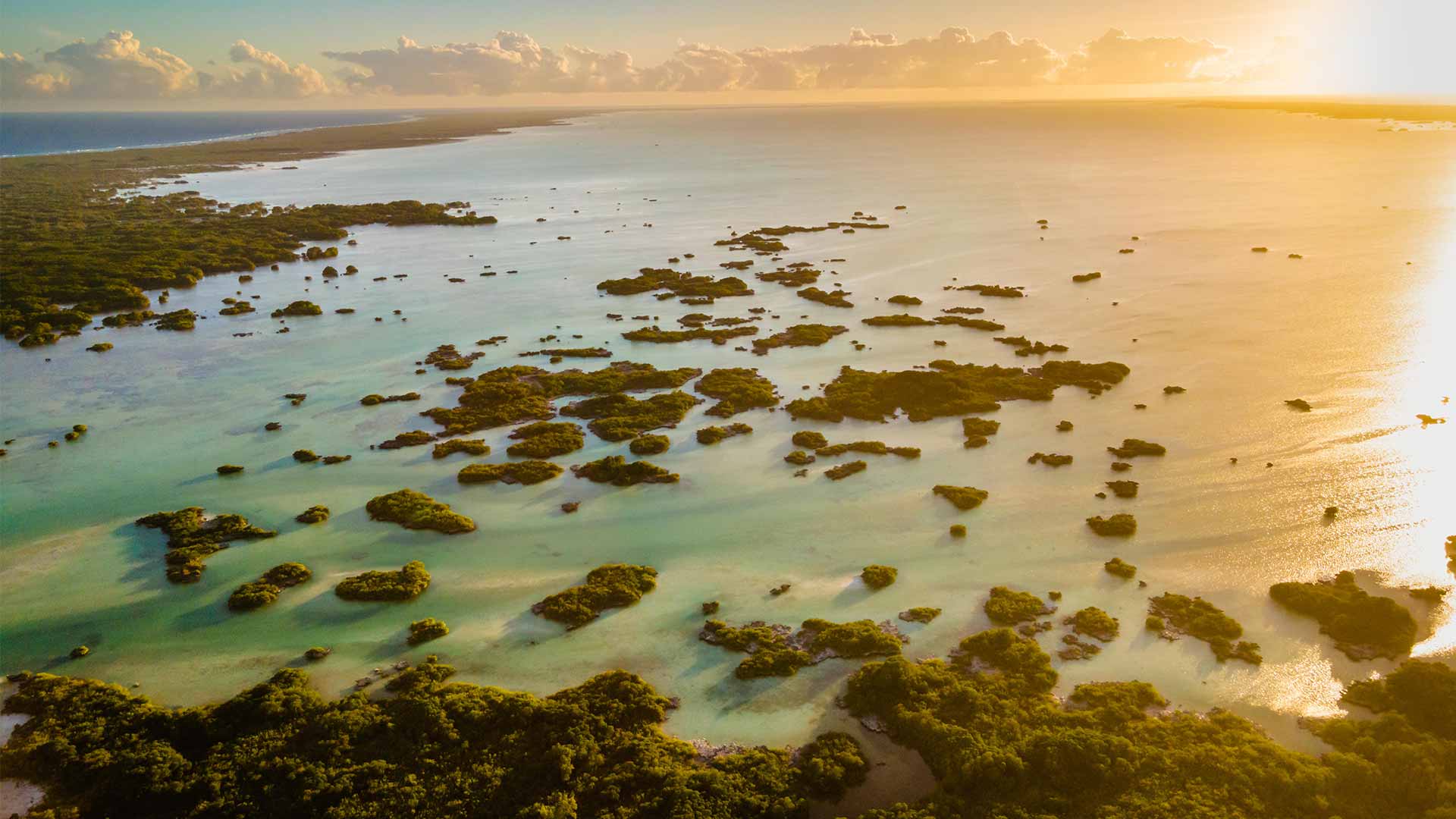

Night falls quickly under the tropics. After collecting several hundred kilos of flip-flops, we never found a matching pair, we decided to climb Dune Jean-Louis, Aldabra’s highest point at twenty meters tall. The sun was about to set. The colors softened, fading into pastel. On one side lay the sea, on the other, dense and tangled vegetation filled with thorny shrubs. From above, it looked like an endless savanna.

Back at camp, dinner took on a special meaning for me: it isn’t every year one celebrates a birthday on a deserted island. When dessert came, Marine, Morgane, and Simon appeared with a chocolate cake kindly baked by Aodren, the ship’s cook. They even thought of a candle. As for gifts, I couldn’t have asked for more: hidden among the expedition supplies were two sculptures, a small map of Corsica and a fish, both made from recycled plastic by Germain and Mélodie, the brilliant creators behind the onboard workshop. A few glasses of rum sealed the evening.

The night was short. I woke several times to the sound of objects falling to the floor, pushed by rats living inside the wooden hut. At six, everyone sat down to bowls of porridge kindly prepared by Yanick. Outside, large crabs were teasing the family of tortoises that had taken up residence by the cabin door. Two hours later, bags were packed and the Plastic Odyssey team began walking west to map the ten kilometers separating the Dune Jean-Louis and Dune de Mess camps.

The packs were heavy, about fifteen kilos each, maybe twenty for the more determined ones like Thibault. Evagno and Yanick, both from the Seychelles Islands Foundation (SIF), the organization that manages and protects Aldabra, led the way. The wind was fierce and constant along Aldabra’s southern coast. Some gusts reach 30 knots (55 km/h). Under such conditions, it was impossible to fly the drone to map the shoreline, but we would have another chance on the return journey, two days later.

Aeolus blew at our backs, pushing us forward and cooling us as the sun beat down. Every bit of skin was covered for protection, arms, legs, face. Everyone walked at their own pace, lost in their thoughts. Like the day before, I made up stories about the flip-flops scattered along the ground. This one, with tribal patterns, might have been a gift from a father to his son for finishing school. That green one perhaps belonged to a teacher who cared deeply for her students’ future. There were few plastic bottles on Aldabra, but among the few we found, some had Chinese labels, others Cyrillic. Who threw them overboard? Given the number of fishing buoys found here, it was hard not to think that tuna fleets passing off the atoll played a role in this pollution. Yet they are not the only ones to blame. Mixed among the debris were toys. Marine had become particularly skilled at spotting small yellow rubber ducks. And then there were the thousands of flip-flops, some child-sized, tiny, heartbreaking reminders of other lives.

We moved in single file. Every thirty minutes, the Seychellois stopped for what Yanick called “un posement.” Everyone took the chance to eat a biscuit and ease the weight from their shoulders. After three and a half hours of walking under the brutal sun, wind, and salt spray, we reached Dune de Mess. The mound rose fifteen meters high, its sand fine as flour and dazzlingly white. It was impossible to look at it without sunglasses, and we all felt as if we had reached the end of the world. Like in the days of the first explorers, the dune was untouched by human presence. No tracks, no footprints. One hesitated to leave any, for fear of spoiling such pristine beauty.

Climbing over the dune, we found the wooden hut half-buried beneath the sand. The entrance had collapsed, forcing us to stoop to get inside. There were two small rooms: one would serve as the kitchen, the other as storage. The mattresses, covered in dust and sand, were in poor condition.

As soon as we arrived, Yanick wanted to start preparing lunch, but the gas line was leaking. Simon patched it with tape, and soon we were enjoying delicious pasta with tuna and lentils. No time to rest. Just after lunch, the SIF team received a message from Francis, the island’s manager: “Meet at 2 p.m. at the Dune de Mess landing station. We’re overloaded. Need help carrying everything.”

The path to the landing point felt endless, the sun now at its zenith. Heading inland meant losing the breeze, and the heat was suffocating. After forty-five minutes of walking across the jagged karst, we finally arrived. The loads to carry were huge, water and food supplies enough to survive in this harsh environment. Balancing on the sharp rocks, we carried jerrycans, full sacks, heavy pack frames, and a stubborn plastic bucket weighing a dozen kilos that sliced into my hands as I gripped it.

Back at camp, tents had to be pitched. While Thibault installed the solar panels on the cabin roof, others wandered along the beach. I climbed to the top of the dune to watch the sun slowly descend. Francis came to see me. In his forties, powerfully built, his head shaved, the island’s manager was a charismatic figure. He sat down and we began to talk.

“I’ve been here for four years,” he said. “My job is to make sure everything runs smoothly for the twenty or so people living on the island. I have to ensure we have enough drinking water, that systems work properly. I also look after everyone’s physical and mental health. Resupply ships only come twice a year, so it’s almost impossible to evacuate anyone in case of emergency. There’s also a lot of administrative work involved.”

He was deeply passionate about Aldabra. Listening to him, it felt as though he knew every corner of the atoll and every danger. “I worked my whole life to get this position,” he continued. “I studied partly in Switzerland, but I always knew I’d come back. I wanted to work on an atoll that was a nature reserve. Aldabra is special. Life here can be tough, but there’s something powerful that connects me to this place. The island is constantly testing its inhabitants. It throws challenges at us, then rewards us with a magnificent sunset, a walk along a dreamlike beach, or the sight of a baby tortoise hatching.”

But the plastic waste weighs on him. “It’s getting worse every year,” Francis said. “We need a global awakening, a solution at the source. This pollution doesn’t stain New York or Paris. It ends up here, in the middle of nowhere. That’s why it’s so important to speak up, to let the world know. I hope Plastic Odyssey will help us clean it all.”

Night had fallen. A dozen tortoises surrounded us. Almost naively, I asked Francis what message Aldabra might want to send to the world. “It would be a cry from the heart,” he said. “I am unique. Protect me.”

Author: Pierre Lepidi, Senior Reporter at Le Monde

Other articles

Day 1: “Aldabra, here we go!”

After spending a few hours at anchor off the Seychelles capital, the vessel set sail in the early afternoon. "Aldabra, here we go!" cheered Pierre-Louis, known to all as "Pilou", the second officer, as he sounded the ship’s horn. Under a cloudless sky, Plastic Odyssey first headed north along the coast of Mahé. Slowly, the island faded into the distance....

Day 2: “Aldabra is a paradise bristling against the invasion of man”

Aldabra has always inspired awe among those lucky enough to reach it. Yet its greatest defender was Commander Jacques-Yves Cousteau (1910–1997). Beyond revealing Aldabra’s coral beauty to the world, he made it his mission to protect it from the various forms of harm caused by humankind....

Day 3: Final preparations before landing on Aldabra

The vessel now moved to the rhythm of landing preparations, and nothing was left to chance. To protect biodiversity, the Seychelles Islands Foundation (SIF), the body responsible for regulating the atoll and issuing permits, requires that all equipment taken ashore on Picard Island be thoroughly cleaned of dust, sand, seeds, and soil....

Day 4: Aldabra, seen from the sky

One of Plastic Odyssey’s missions is to map the areas where 513 tons of plastic waste were recorded during a scientific expedition in 2020. Driven by the trade winds, these piles have accumulated along the southern and eastern shores of the atoll, over roughly fifty kilometers. Some of these zones, as satellite images show, are extremely difficult to reach....

Day 5: Aldabra, the challenge of water

The heat was oppressive, almost suffocating. The first challenge was to get the seawater desalination unit running to rehydrate. "Water is life. The first priority in any survival situation is always access to water," explained Thibault, engineer aboard Plastic Odyssey. Since there are no natural sources on Aldabra, the scientific team relies exclusively on filtered rainwater for their daily needs....

Day 6: East of Aldabra, a lunar landscape swept by the trade winds

After waking, the Plastic Odyssey team decided to watch the sunrise from the top of the dune beside the DJL camp. Rising about twenty meters high, it is the atoll’s highest point. From up there, nature came alive in calm and color. Aldabra stretched out in every direction. The first light of day glowed orange and gold, as if the island were trying to seduce us....

Day 7: Aldabra does not give itself away, It must be earned

To confront Aldabra is to endure the island’s harsh conditions, but every effort is rewarded. A meeting with a tortoise, a sunset, a breathtaking landscape, the island gives back to those who care for it. But it never gives itself easily. It must be earned....

Day 8: Aldabra asks to be protected

Night had fallen. A dozen tortoises surrounded us. Almost naively, I asked Francis, the island's manager, what message Aldabra might want to send to the world. "It would be a cry from the heart," he said. "I am unique. Protect me."...

Day 9: Life Among Aldabra’s Giant Tortoises

The sea turtle reaches the plastic debris: she skirts a fishing buoy, crushes a plastic bottle. Farther on, a tire, a few jerrycans, some sandals. Watching her struggle through this apocalyptic landscape feels unreal, deeply moving....

Day 10: Mission accomplished for Plastic Odyssey on Aldabra

The Plastic Odyssey is expected off Dune Jean-Louis at 10 a.m. to test the extraction of half a ton of plastic waste using a floating platform made of jerrycans. The barge will shuttle between the vessel and the shore. But the sea is rough, and the wind is strong. Will the extraction be possible? Tension and uncertainty fill the air....