The Plastic Odyssey is expected off Dune Jean-Louis at 10 a.m. to test the extraction of half a ton of plastic waste using a floating platform made of jerrycans. The barge will shuttle between the vessel and the shore. But the sea is rough, and the wind is strong. Will the extraction be possible? Tension and uncertainty fill the air.

The night was short. First because strong winds blew relentlessly across the Dune de Mess camp, making the tent’s flysheet flap loudly against the frame. But that wasn’t all. At dawn, a crab came to gently brush against my head. Luckily, the fabric was taut enough to stop its thick claws from catching an ear. The crustacean then tried to climb onto the tent poles. Without success.

It is now 7 a.m., and the camp slowly wakes. Marine, the onboard reporter, spots baby turtles on the beach. They have just hatched. Aldabra offers us another glimpse of life in fast motion: after blessing us yesterday with the nesting, the atoll now lets us witness the hatching itself.

In the first moments of their lives, the tiny turtles flail in every direction. They are clumsy, awkwardly trying to reach the sea about twenty meters away. But obstacles abound. First, they must cross a strip of plastic waste: stranded jerrycans, flip-flops, fishing buoys. Worse still, just above the nest, an ibis has found the perfect spot for a feast. Lurking a short distance away, it watches, then plunges its curved beak into the sand to catch the hatchlings, sometimes even before they reach daylight. With two or three quick movements, the bird swallows them whole. Occasionally, it spits one back out, half-dead, and leaves it behind.

By some miracle, one small turtle escapes the predator’s gaze. Against all odds, she makes her way toward the sea unnoticed. “A lucky one,” I think. I decide to call her Fortuna, goddess of fortune.

The bird is now far from my little protégé, whose tiny flippers move frantically across the sand. She pushes forward without hesitation, never looking back. Fortuna steps over flip-flops, tumbles onto her shell, rights herself, and continues without pausing. The first minutes of her life are already a test of endurance. Amid the waste, it’s an obstacle course, a nightmare. Yet she seems to know that only the ocean can save her. Behind her, the ibis keeps hunting, methodically slaughtering her siblings.

Fortuna reaches the waterline. A first wave violently tosses her fragile thirty-gram body back onto the beach. Then a second, even stronger. The third, smaller than the others, finally carries her into the vastness of the ocean. Pride wells up inside us. Does she now feel calm? Relief? The tiny turtle drifts farther out to sea until we lose sight of her. I can’t help but wonder: where will she go? Will luck stay on Fortuna’s side? What will become of her?

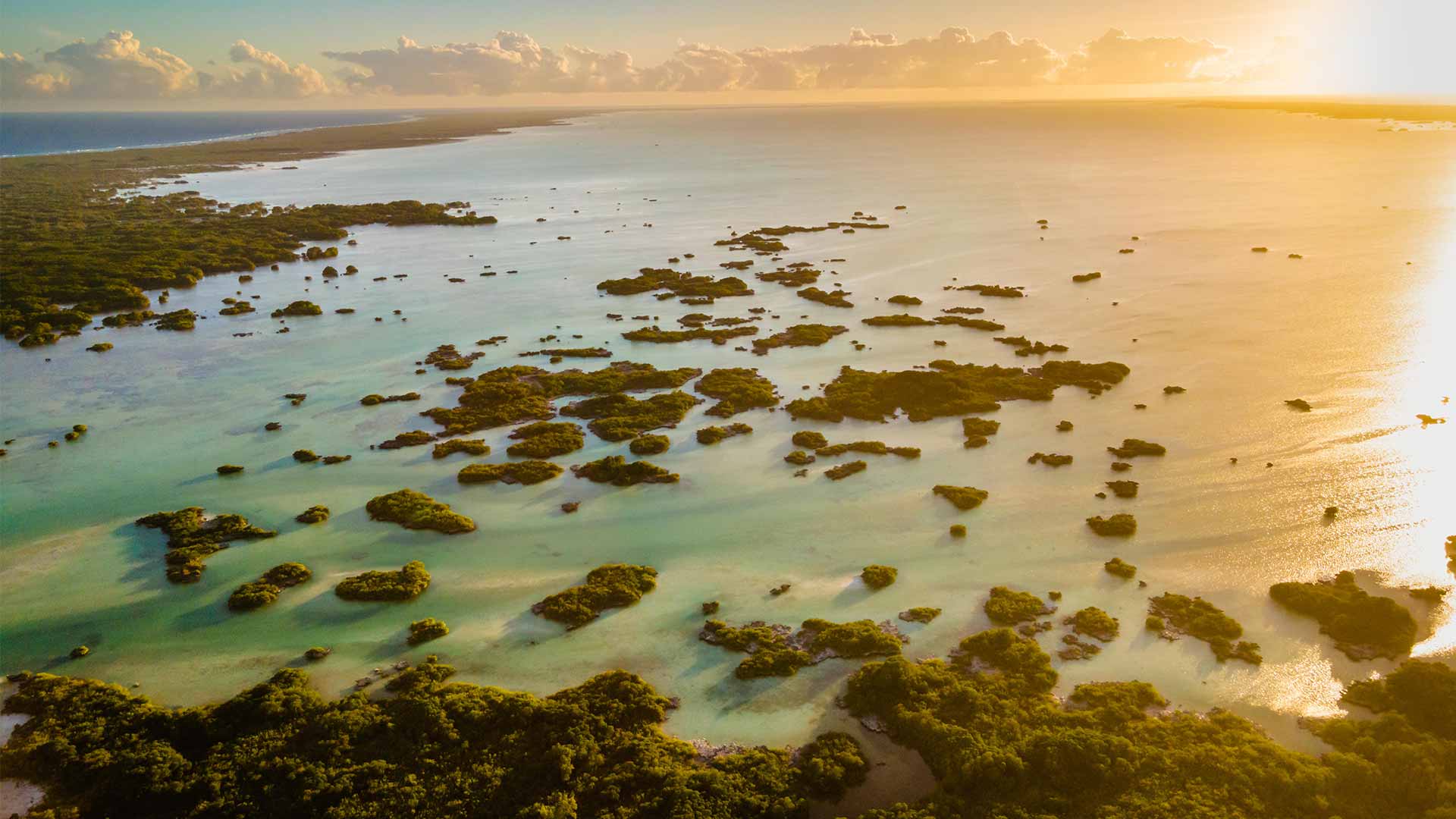

It’s time to pack up camp. Around 8:30 a.m., we begin our journey east toward Dune Jean-Louis (DJL). Will we ever return to Dune de Mess? During a conversation the night before, we agreed that fewer people had stood atop Everest than at the foot of this remote dune on Aldabra, the UNESCO World Heritage atoll.

The wind has eased, allowing Thibault to fly the drone and map this southern stretch of the atoll, something he hadn’t been able to do on the way out. This ten-kilometer section was the final missing piece.

Now we walk into the wind, still carrying about fifteen kilos each. Our feet sink into the sand, sea spray lashes our faces. When the path turns to the treacherous karst rock, we tread carefully, the sharp stone slicing through even the soles of our shoes. Everyone is silent, lost in thought. Yanick, our steward, leads the way, proudly wearing his PSG jersey, drawing good-natured teasing from the southerners in the group.

The afternoon is devoted to collecting debris around Dune Jean-Louis. We gather jerrycans, dozens of fishing buoys, and hundreds of colorful flip-flops to later send to Ocean Sole, a Kenyan NGO that transforms them into sculptures.

How can hundreds of tons of waste be hauled over the jagged karst barrier that encircles the atoll? Expedition leader Simon Bernard has come up with an ingenious solution: a makeshift bamboo slide built by linking hollow stems together. Late in the afternoon, he tests the idea on the beach, and it works. “The fishing buoys and jerrycans will be lashed together and towed from the sea,” he explains enthusiastically. “We’ll just need to build these slides at each extraction site!”

As evening falls, Dino, one of the two soldiers stationed on the atoll with the Seychelles Special Forces, lights a fire in front of camp. Tonight’s dinner: a magnificent trevally caught earlier in the day. Night settles in. We gather around the flames, watching them dance, sharing memories.

The next morning, there’s no time to linger. The Plastic Odyssey is expected off Dune Jean-Louis at 10 a.m. to test the extraction of half a ton of plastic waste using a floating platform made of jerrycans. The barge will shuttle between the vessel and the shore. But the sea is rough, and the wind is strong. Will the extraction be possible? Tension and uncertainty fill the air.

At the appointed time, the ship, anchored the night before near the scientific base on the western side of the atoll, arrives right on schedule. Relief. Now the platform must be brought ashore. Since it’s too dangerous for the Zodiac to tow it directly to the beach, the plan is to send out a fishing line with the drone, then reel it back to shore using a spool, allowing a rope to be pulled in. Once secured, a winch anchored to a rock will haul the platform in. But after twenty suspenseful minutes, the fishing line snaps.

Undeterred, Simon and Thibault pull on their fins and dive in to recover the rope. The sea is swelling, the area is known for its sharks, and anxiety rises on the beach. Swimming against the wind, they finally reach the platform after fifteen long minutes. Now they must bring the line back to shore, but the current is too strong, pulling them away from land. After several tense minutes, they turn back. Failure. Onshore, Francis, the island manager, is furious.

“Do you still have eyes on Simon?” asks Pierre-Louis, known as Pilou, the second officer, over the radio. “We’ve lost sight of him.” Several minutes of panic follow. The tension is unbearable. Then, suddenly, in the middle of the waves, Simon reappears. He reaches the platform with Thibault. The two combat swimmers are safe. They return to Plastic Odyssey with Pilou and Megane, who, just hours earlier, had seen a lifeboat engine catch fire right before her eyes. Some days, nothing goes as planned. “Let’s have lunch on the ship and figure it out afterward,” Simon suggests over the radio.

The solution is to wait for the rising tide around 4 p.m. Using the Zodiac, Pilou tows the platform toward the beach. Everyone grabs hold and pulls it up onto the sand. Within minutes, the 500 kilos of plastic waste are loaded onto the barge and securely strapped down. The Zodiac begins towing. The tension peaks. A massive wave approaches the platform at a sharp angle. Will it capsize and send all the collected waste back into the sea? The bow lifts, points skyward, then crashes flat with a deafening thud before slowly gliding away. The wave has passed. Nothing stands between the barge and the ship now.

On the beach, applause erupts. We embrace, overcome with relief. What a moment of pride to see hundreds of kilos of waste finally leaving Aldabra. These are the first to be extracted by Plastic Odyssey.

As evening falls, we welcome several scientists from the base, including Martin, who had kindly greeted us during our first days here. After all the emotion of the day, the mood is joyful again. The reggae is back too: Morgan Heritage, Steel Pulse, and of course, Bob.

Because of the tide, we must wait until the next evening to leave Dune Jean-Louis through the lagoon. During the day, we pack up the camp, and according to tradition, everyone signs their name on the cabin door to mark their passage. The doors of the atoll are closing. As a parting gift, the Plastic Odyssey team leaves the scientific base a bench painted in the colors of the Seychelles flag and two chairs. The furniture, crafted overnight by Germain and Mélodie from Aldabra’s recycled plastic, will stay behind as a symbol. The farewells with Francis, Yanick, Martin, and the other residents of the island are deeply moving.

Plastic Odyssey now heads north toward Mahé, the main island of the Seychelles. It is late afternoon. Sitting at the bow, Simon Bernard reflects on the expedition. “Nothing was easy, and we could have failed many times because we had no margin for error,” he says. “Every day was full, and we may have underestimated the size of the atoll and the logistics it required, given how rough the terrain is. But it’s a success: we managed to map the most polluted sites and extract several hundred kilos of waste. It’s only the beginning; we hope to remove it all in two years.”

Days pass, and life aboard returns to its rhythm. Everyone slips back into their habits. Jojo, the second mechanic, is always rushing somewhere. Désiré walks the corridors with his tools. During her breaks, Megane paints watercolors. Aodren simmers dishes in the galley. In the evening, Germain and Mélodie fish off the stern. Late at night, on the bridge, Lena listens to podcasts.

Aldabra remains in everyone’s mind. The island has a pull, something that ties you to it and makes you want to fight for its protection. Those who have been there have always felt it. In 1874, naturalist Charles Darwin implored the British authorities to protect Aldabra’s tortoises: “We recommend to the Colonial Government the safeguarding and protection of the giant tortoises, not so much for their usefulness as for their immense scientific interest,” he wrote. “We trust that the current government will find a way to save the last remaining specimens of this animal.” Nearly a century later, Commander Cousteau proposed taking over the Aldabra concession himself to make it a nature reserve. He even met with Churchill to plead his case, but in vain. Today, the atoll is still under threat. A proposed luxury resort on nearby Assumption Island, just forty kilometers away, raises serious concern. And then there is all that plastic, which will one day have to be removed.

Plastic Odyssey enters the Port of Victoria, the capital of the Seychelles. On the bridge, Captain Yoann gives instructions to Patrick, the bosun, who works at the bow securing the vessel. Minutes later, in the engine room, Simon, the chief engineer, shuts down the ship’s two engines, thinking fondly of his children, a ritual at the end of every voyage.

The next day, Simon Bernard hands the Seychelles Islands Foundation (SIF), the organization managing Aldabra, a detailed expedition report along with small gifts: keychains and soap dishes made from plastic collected on the atoll. The welcome is warm. On both sides, there is a shared will to go further and protect Aldabra. Later that afternoon, Kyle, from the Seychellois NGO Brikole, receives the remaining tons of recovered plastic. The goal: to recycle, always. And to keep looking toward the horizon.

The End.

Author: Pierre Lepidi, Senior Reporter at Le Monde

Other articles

Day 1: “Aldabra, here we go!”

After spending a few hours at anchor off the Seychelles capital, the vessel set sail in the early afternoon. "Aldabra, here we go!" cheered Pierre-Louis, known to all as "Pilou", the second officer, as he sounded the ship’s horn. Under a cloudless sky, Plastic Odyssey first headed north along the coast of Mahé. Slowly, the island faded into the distance....

Day 2: “Aldabra is a paradise bristling against the invasion of man”

Aldabra has always inspired awe among those lucky enough to reach it. Yet its greatest defender was Commander Jacques-Yves Cousteau (1910–1997). Beyond revealing Aldabra’s coral beauty to the world, he made it his mission to protect it from the various forms of harm caused by humankind....

Day 3: Final preparations before landing on Aldabra

The vessel now moved to the rhythm of landing preparations, and nothing was left to chance. To protect biodiversity, the Seychelles Islands Foundation (SIF), the body responsible for regulating the atoll and issuing permits, requires that all equipment taken ashore on Picard Island be thoroughly cleaned of dust, sand, seeds, and soil....

Day 4: Aldabra, seen from the sky

One of Plastic Odyssey’s missions is to map the areas where 513 tons of plastic waste were recorded during a scientific expedition in 2020. Driven by the trade winds, these piles have accumulated along the southern and eastern shores of the atoll, over roughly fifty kilometers. Some of these zones, as satellite images show, are extremely difficult to reach....

Day 5: Aldabra, the challenge of water

The heat was oppressive, almost suffocating. The first challenge was to get the seawater desalination unit running to rehydrate. "Water is life. The first priority in any survival situation is always access to water," explained Thibault, engineer aboard Plastic Odyssey. Since there are no natural sources on Aldabra, the scientific team relies exclusively on filtered rainwater for their daily needs....

Day 6: East of Aldabra, a lunar landscape swept by the trade winds

After waking, the Plastic Odyssey team decided to watch the sunrise from the top of the dune beside the DJL camp. Rising about twenty meters high, it is the atoll’s highest point. From up there, nature came alive in calm and color. Aldabra stretched out in every direction. The first light of day glowed orange and gold, as if the island were trying to seduce us....

Day 7: Aldabra does not give itself away, It must be earned

To confront Aldabra is to endure the island’s harsh conditions, but every effort is rewarded. A meeting with a tortoise, a sunset, a breathtaking landscape, the island gives back to those who care for it. But it never gives itself easily. It must be earned....

Day 8: Aldabra asks to be protected

Night had fallen. A dozen tortoises surrounded us. Almost naively, I asked Francis, the island's manager, what message Aldabra might want to send to the world. "It would be a cry from the heart," he said. "I am unique. Protect me."...

Day 9: Life Among Aldabra’s Giant Tortoises

The sea turtle reaches the plastic debris: she skirts a fishing buoy, crushes a plastic bottle. Farther on, a tire, a few jerrycans, some sandals. Watching her struggle through this apocalyptic landscape feels unreal, deeply moving....

Day 10: Mission accomplished for Plastic Odyssey on Aldabra

The Plastic Odyssey is expected off Dune Jean-Louis at 10 a.m. to test the extraction of half a ton of plastic waste using a floating platform made of jerrycans. The barge will shuttle between the vessel and the shore. But the sea is rough, and the wind is strong. Will the extraction be possible? Tension and uncertainty fill the air....