The vessel now moved to the rhythm of landing preparations, and nothing was left to chance. To protect biodiversity, the Seychelles Islands Foundation (SIF), the body responsible for regulating the atoll and issuing permits, requires that all equipment taken ashore on Picard Island be thoroughly cleaned of dust, sand, seeds, and soil.

Aboard Plastic Odyssey, time seemed to stand still. It was Tuesday, October 8, early evening. The sun was slowly descending, playing hide-and-seek with the clouds. Its last rays bathed the scene in a soft orange glow, an exceptional light. At the bow, Meghane, Maluha, and Morgane, respectively deckhand, diver, and stopover coordinator, had unrolled their mats for a yoga session, watching the spectacle unfold before them. Alone, facing the immensity of the ocean.

At the same moment on the bridge, Pierre-Louis, known as “Pilou,” the second officer, hummed along to songs by Georges Brassens, Gilbert O’Sullivan, and Mayra Andrade. The vessel swayed gently to the rhythm of the morna, Cape Verde’s soulful music. Around 7 p.m., the sun disappeared beyond the horizon, and life aboard resumed its normal course.

“We can see Aldabra on the chart!” exclaimed Morgane the following morning as she entered the command post. “We should be at anchor around nine tomorrow morning,” replied Yoann, the captain. “We’ve got 160 miles to go.”

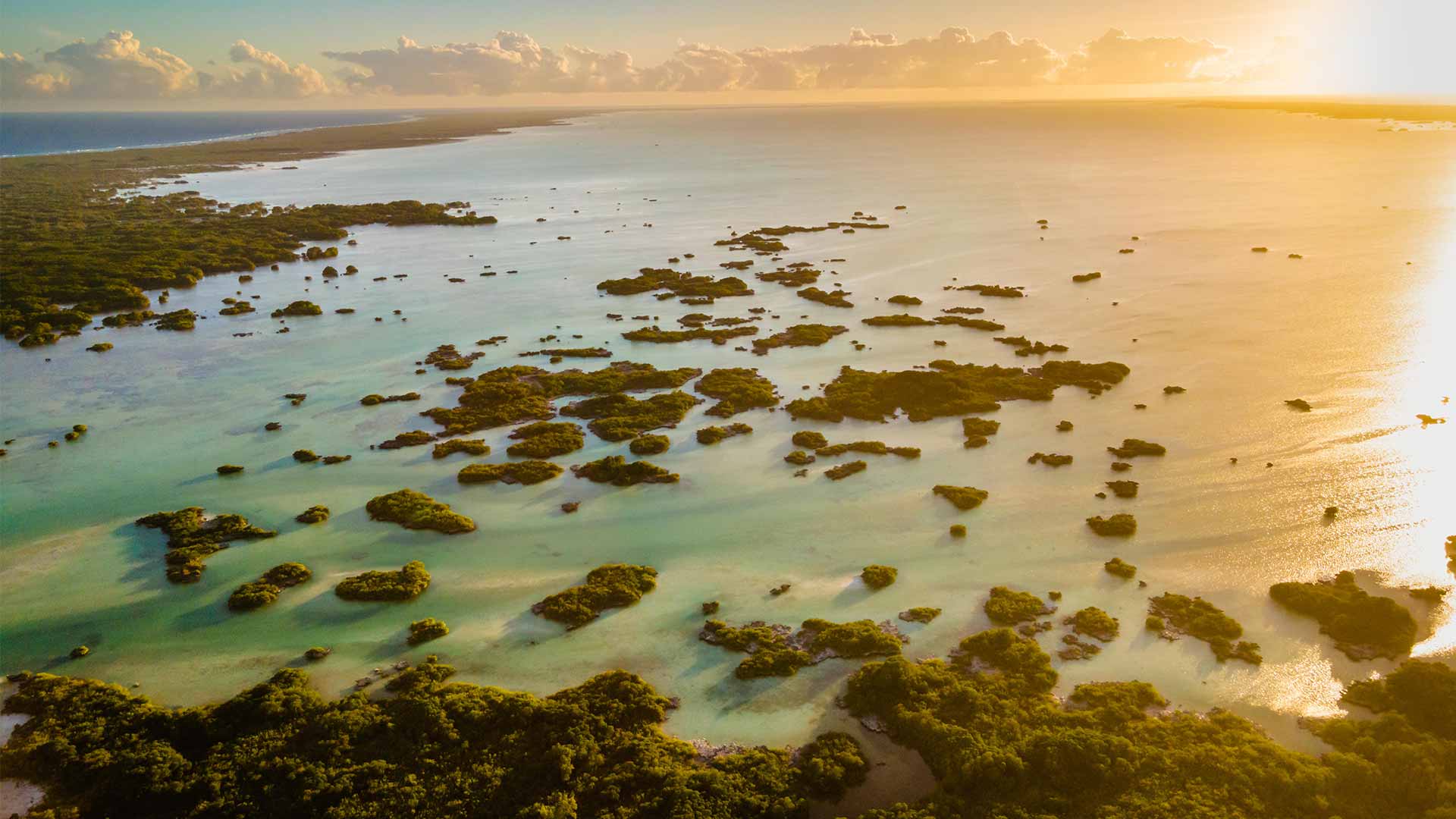

Lost in the middle of the Indian Ocean, Aldabra is a Seychellois atoll made up of four islands: Grande Terre, Malabar, Polymnie, and Picard. Its surface area is about one and a half times the size of Paris. Since 1982, it has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and the organization signed a partnership with Plastic Odyssey last spring. A true natural paradise, Aldabra is now threatened by marine pollution. According to a 2020 study conducted by a team of researchers, the atoll holds nearly 513 tons of plastic waste. “It’s one of the most polluted atolls in the world,” explained Simon Bernard, Plastic Odyssey’s expedition leader and shipowner. “This ten-day mission will aim to map the most polluted sites and explore potential methods for removing the waste.”

The vessel now moved to the rhythm of landing preparations, and nothing was left to chance. To protect biodiversity, the Seychelles Islands Foundation (SIF), the body responsible for regulating the atoll and issuing permits, requires that all equipment taken ashore on Picard Island, where a small scientific base hosts about ten people, be thoroughly cleaned of dust, sand, seeds, and soil. This bio-disinfection process aims to minimize the risk of biological contamination. In the conference room or out on deck, sleeping bags, toiletries, and shoes were all being meticulously scrubbed. Before disembarkation, a team from SIF would come aboard to inspect everything.

Since departing from Victoria, the capital of the Seychelles, the crew’s mobilization had been total. In their onboard workshop, Germain and Mélodie had designed protective soles and overshoes made from recycled tires. These would allow those landing ashore, two teams of five people each authorized between October 10 and 18, to move safely across all kinds of terrain, even the most hostile. “Everywhere, the ground is a chaos of sharp coral, bare, riddled with crevices, pierced with pits that are as many traps,” wrote Commander Cousteau in Aldabra, Coral Sanctuary (IMA Ed.) during his 1954 expedition. “Everywhere, a jungle of thorny, impenetrable shrubs.” Germain and Mélodie had also tested and repaired all the equipment: the solar-powered water desalination unit, the winch, and more. “We’ll use drones to map the waste,” explained Thibault, head of incubation programs. “But their range is limited, and the area to cover is immense. We also have to account for the difficulty of moving around. In short, there are many hypotheses, and just as many unknowns.”

The expedition had other goals beyond waste mapping. “We hope to collect one ton of plastic debris to produce planks and furniture aboard the vessel,” added Thibault, who also oversees the documentation of recycling projects. “For that, we’ll be working with Brikole, a Seychellois company. Another batch will go to artists who specialize in recycled plastic works.” And then there are the flip-flops. According to the 2020 study, six tons of them litter Aldabra. Some of these recovered sandals will be sent to Ocean Sole, a Kenyan NGO that specializes in this type of recycling.

Plastic Odyssey was now in the heart of the night. The sea had risen and was tossing the vessel in every direction. In the mess hall, a stack of plates slid from its shelf and shattered on the floor. In the conference room, the printer went flying with a loud crash. “We’re changing course and heading west,” assured Yoann on the bridge. “The waves won’t be hitting us broadside anymore but from astern. We’ll surf them instead.” A message was sent to the entire crew on WhatsApp: no access to exterior decks for safety reasons.

After the rough night, the sea had calmed by morning. Around nine o’clock, Aldabra appeared in the distance. “After several days at sea, it’s always moving to see land again,” said Morgane with a smile. In his travelogue, Commander Cousteau wrote that Aldabra “does not emerge from the horizon abruptly,” but rather “reveals itself to the watchful eye as a greenish reflection in the sky.” This morning, a faint halo indeed hovered above the atoll. The name Aldabra, given by Arab sailors, is thought to have been inspired by this very glow, “khadraa” meaning “the green” in Arabic.

What will we find there? What solutions will be envisioned for removing the waste? How will communications be established between the teams on land and the vessel? Will the forecasted wind allow the drones to fly? Questions abound, and excitement runs high.

It was 10:30 a.m. when Plastic Odyssey dropped anchor off Picard Island. Aboard the Calypso, Commander Cousteau had done the same nearly seventy years earlier. “The rising sun lights a low, jagged coast covered with bushes and tall trees,” wrote Gustave Cherbonnier, a biologist from the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris who joined that expedition. “We sail slowly along the immense and mysterious Aldabra. Now that we are closer, we can better distinguish its menacing shores of dead coral. The branches rise like sharp spikes, towering several meters above a raging sea that lashes the ground with powerful waves, bursts into immense sheets of foam, and rushes into deep, low caves.” The scene is exactly the same, seventy years later. Here again, time seems to have stopped.

Author: Pierre Lepidi, Senior Reporter at Le Monde

Other articles

Day 1: “Aldabra, here we go!”

After spending a few hours at anchor off the Seychelles capital, the vessel set sail in the early afternoon. "Aldabra, here we go!" cheered Pierre-Louis, known to all as "Pilou", the second officer, as he sounded the ship’s horn. Under a cloudless sky, Plastic Odyssey first headed north along the coast of Mahé. Slowly, the island faded into the distance....

Day 2: “Aldabra is a paradise bristling against the invasion of man”

Aldabra has always inspired awe among those lucky enough to reach it. Yet its greatest defender was Commander Jacques-Yves Cousteau (1910–1997). Beyond revealing Aldabra’s coral beauty to the world, he made it his mission to protect it from the various forms of harm caused by humankind....

Day 3: Final preparations before landing on Aldabra

The vessel now moved to the rhythm of landing preparations, and nothing was left to chance. To protect biodiversity, the Seychelles Islands Foundation (SIF), the body responsible for regulating the atoll and issuing permits, requires that all equipment taken ashore on Picard Island be thoroughly cleaned of dust, sand, seeds, and soil....

Day 4: Aldabra, seen from the sky

One of Plastic Odyssey’s missions is to map the areas where 513 tons of plastic waste were recorded during a scientific expedition in 2020. Driven by the trade winds, these piles have accumulated along the southern and eastern shores of the atoll, over roughly fifty kilometers. Some of these zones, as satellite images show, are extremely difficult to reach....

Day 5: Aldabra, the challenge of water

The heat was oppressive, almost suffocating. The first challenge was to get the seawater desalination unit running to rehydrate. "Water is life. The first priority in any survival situation is always access to water," explained Thibault, engineer aboard Plastic Odyssey. Since there are no natural sources on Aldabra, the scientific team relies exclusively on filtered rainwater for their daily needs....

Day 6: East of Aldabra, a lunar landscape swept by the trade winds

After waking, the Plastic Odyssey team decided to watch the sunrise from the top of the dune beside the DJL camp. Rising about twenty meters high, it is the atoll’s highest point. From up there, nature came alive in calm and color. Aldabra stretched out in every direction. The first light of day glowed orange and gold, as if the island were trying to seduce us....

Day 7: Aldabra does not give itself away, It must be earned

To confront Aldabra is to endure the island’s harsh conditions, but every effort is rewarded. A meeting with a tortoise, a sunset, a breathtaking landscape, the island gives back to those who care for it. But it never gives itself easily. It must be earned....

Day 8: Aldabra asks to be protected

Night had fallen. A dozen tortoises surrounded us. Almost naively, I asked Francis, the island's manager, what message Aldabra might want to send to the world. "It would be a cry from the heart," he said. "I am unique. Protect me."...

Day 9: Life Among Aldabra’s Giant Tortoises

The sea turtle reaches the plastic debris: she skirts a fishing buoy, crushes a plastic bottle. Farther on, a tire, a few jerrycans, some sandals. Watching her struggle through this apocalyptic landscape feels unreal, deeply moving....

Day 10: Mission accomplished for Plastic Odyssey on Aldabra

The Plastic Odyssey is expected off Dune Jean-Louis at 10 a.m. to test the extraction of half a ton of plastic waste using a floating platform made of jerrycans. The barge will shuttle between the vessel and the shore. But the sea is rough, and the wind is strong. Will the extraction be possible? Tension and uncertainty fill the air....