One of Plastic Odyssey’s missions is to map the areas where 513 tons of plastic waste were recorded during a scientific expedition in 2020. Driven by the trade winds, these piles have accumulated along the southern and eastern shores of the atoll, over roughly fifty kilometers. Some of these zones, as satellite images show, are extremely difficult to reach.

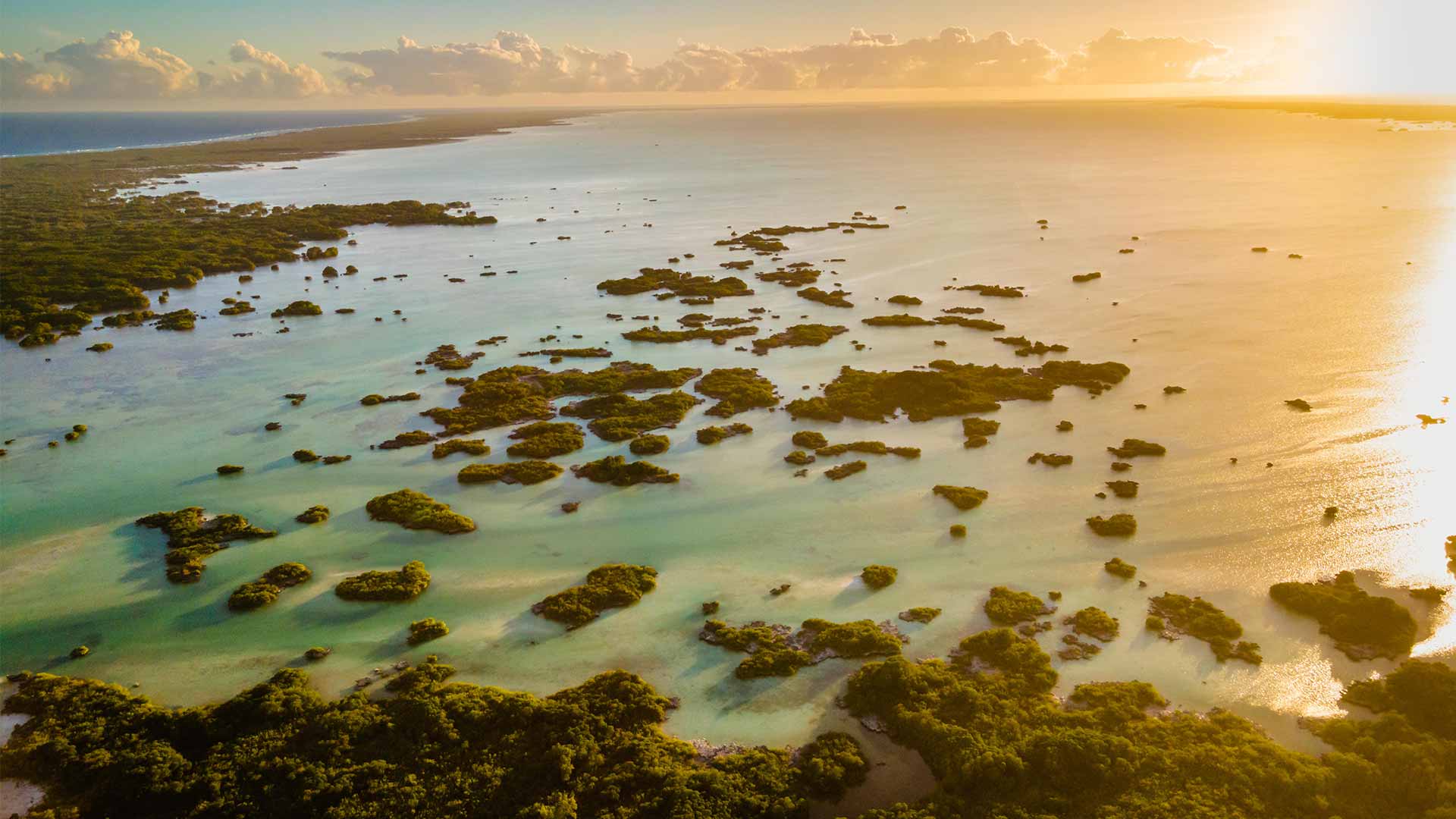

Plastic Odyssey is now anchored about fifty meters from Aldabra. On the foredeck, no one tires of admiring the Seychellois atoll, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1982. At sunset, white sand beaches and secluded coves line a translucent sea. It is a dreamlike setting, the kind of image that could grace a computer or phone wallpaper. Yet farther along, the landscape seems entirely different, even hostile. The coast is made of steep cliffs and razor-sharp coral. Just beyond, thorn-covered shrubs stretch toward the sky. The vegetation is dense and forms an impenetrable barrier.

One of Plastic Odyssey’s missions is to map the areas where 513 tons of plastic waste were recorded during a scientific expedition in 2020. Driven by the trade winds, these piles have accumulated along the southern and eastern shores of the atoll, over roughly fifty kilometers. Some of these zones, as satellite images show, are extremely difficult to reach. There is also no drinking water or food available on Aldabra. To carry out a first detailed survey, drones must therefore be deployed.

On Friday, October 10, test flights were conducted from the ship’s bow, but one of the drones lost signal after just a few minutes. Fortunately, it landed a few cables away from the Aldabra base, where a team of about ten people currently resides. It was retrieved and brought back aboard by Martin and Alice, two French scientists who arrived on the island in spring 2024 to study the impact of invasive species (cats, rats, and others) and to ensure the biosecurity of all Plastic Odyssey expedition equipment. The goal of this operation is to reduce contamination risks by eliminating dust, sand, soil, seeds, and even ants from everything taken ashore onto the island, a sanctuary of biodiversity. “It is a refuge for more than 400 endemic species and subspecies,” UNESCO notes. “Among them is the world’s largest population of giant tortoises, with more than 100,000 individuals.”

Every object, even brand-new ones, is carefully inspected, especially Velcro straps, which are considered “seed traps.” “It’s better to spend ten minutes inspecting every corner of a suitcase than ten years eradicating an invasive species,” explained Martin, team leader with the Seychelles Islands Foundation (SIF), the organization responsible for regulating the atoll. “Several animal species have already endangered Aldabra’s biodiversity. Eliminating the goats that humans brought here took nearly two decades, but it was necessary because they fed on the same grass as the tortoises. On other islands, cats have caused the disappearance of endemic species.” There are thought to be nearly six hundred cats on the atoll.

With favorable weather conditions just before noon, Plastic Odyssey raised anchor and set course south, toward Grande Terre, the largest of the four islands. The first drone was piloted from the stern by Alexis, a professional diver, and his daughter, Maluha. A second drone was launched from a Zodiac carrying Simon Bernard, expedition leader and owner of Plastic Odyssey, Marine, head of media, and Thibault, engineer. For several hours, their drones photographed the most inaccessible stretches of the coast, taking pictures every twenty meters.

On the control screens, the images were breathtaking. Throughout the afternoon, the coral reef shifted in color, from blue to green, then from green back to blue. Seen from the sky, the lagoon glowed with an emerald hue, contrasting with the exposed patches of land visible in the shallows.

The drones captured hundreds of photos. From above the clouds, Aldabra looked fragile, lost in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Yet the atoll is vast, nearly one and a half times the size of Paris. “We were a little surprised by its scale when we arrived,” admitted Simon Bernard. “From the satellite images, we hadn’t realized there were cliffs, sometimes ten meters high, with powerful waves crashing at their base. What’s astonishing is that the waste has accumulated above the cliffs, thrown up by high tides. There aren’t big piles of it, but it’s scattered across long stretches. The whole environment is strikingly wild.”

The objective, to photograph the ten kilometers most difficult to reach on foot, was achieved by early evening. “We can be proud,” said Simon Bernard. “It was a tough job because we did everything manually. Aboard the Zodiac, retrieving the drone was often risky, with two-meter waves, but we brought both aircraft back safely, and that’s a relief.” The photos will now be sent to a company specializing in image analysis, to identify the types of plastic waste present on Aldabra, estimate their total weight, and study how they might be removed. Later that night, after three hours of navigation, Plastic Odyssey returned to anchor off Picard Island, the westernmost of the four.

The next morning, around 7 a.m., the mess hall was full for breakfast. Excitement filled the air: a team of five people would set foot on Aldabra. An hour later, the Frigate, a launch from the island’s scientific base that had once been seized from Somali pirates, landed on a white sand beach. Smiling, one by one, they stepped ashore.

It was pure wonder. A light breeze stirred the fronds of a palm tree. The sea was calm, the sand fine, a turtle slid gracefully into the water. Everything was serene. It was our first step on Aldabra, a giant leap for Plastic Odyssey.

Author: Pierre Lepidi, Senior Reporter at Le Monde

Other articles

Day 1: “Aldabra, here we go!”

After spending a few hours at anchor off the Seychelles capital, the vessel set sail in the early afternoon. "Aldabra, here we go!" cheered Pierre-Louis, known to all as "Pilou", the second officer, as he sounded the ship’s horn. Under a cloudless sky, Plastic Odyssey first headed north along the coast of Mahé. Slowly, the island faded into the distance....

Day 2: “Aldabra is a paradise bristling against the invasion of man”

Aldabra has always inspired awe among those lucky enough to reach it. Yet its greatest defender was Commander Jacques-Yves Cousteau (1910–1997). Beyond revealing Aldabra’s coral beauty to the world, he made it his mission to protect it from the various forms of harm caused by humankind....

Day 3: Final preparations before landing on Aldabra

The vessel now moved to the rhythm of landing preparations, and nothing was left to chance. To protect biodiversity, the Seychelles Islands Foundation (SIF), the body responsible for regulating the atoll and issuing permits, requires that all equipment taken ashore on Picard Island be thoroughly cleaned of dust, sand, seeds, and soil....

Day 4: Aldabra, seen from the sky

One of Plastic Odyssey’s missions is to map the areas where 513 tons of plastic waste were recorded during a scientific expedition in 2020. Driven by the trade winds, these piles have accumulated along the southern and eastern shores of the atoll, over roughly fifty kilometers. Some of these zones, as satellite images show, are extremely difficult to reach....

Day 5: Aldabra, the challenge of water

The heat was oppressive, almost suffocating. The first challenge was to get the seawater desalination unit running to rehydrate. "Water is life. The first priority in any survival situation is always access to water," explained Thibault, engineer aboard Plastic Odyssey. Since there are no natural sources on Aldabra, the scientific team relies exclusively on filtered rainwater for their daily needs....

Day 6: East of Aldabra, a lunar landscape swept by the trade winds

After waking, the Plastic Odyssey team decided to watch the sunrise from the top of the dune beside the DJL camp. Rising about twenty meters high, it is the atoll’s highest point. From up there, nature came alive in calm and color. Aldabra stretched out in every direction. The first light of day glowed orange and gold, as if the island were trying to seduce us....

Day 7: Aldabra does not give itself away, It must be earned

To confront Aldabra is to endure the island’s harsh conditions, but every effort is rewarded. A meeting with a tortoise, a sunset, a breathtaking landscape, the island gives back to those who care for it. But it never gives itself easily. It must be earned....

Day 8: Aldabra asks to be protected

Night had fallen. A dozen tortoises surrounded us. Almost naively, I asked Francis, the island's manager, what message Aldabra might want to send to the world. "It would be a cry from the heart," he said. "I am unique. Protect me."...

Day 9: Life Among Aldabra’s Giant Tortoises

The sea turtle reaches the plastic debris: she skirts a fishing buoy, crushes a plastic bottle. Farther on, a tire, a few jerrycans, some sandals. Watching her struggle through this apocalyptic landscape feels unreal, deeply moving....

Day 10: Mission accomplished for Plastic Odyssey on Aldabra

The Plastic Odyssey is expected off Dune Jean-Louis at 10 a.m. to test the extraction of half a ton of plastic waste using a floating platform made of jerrycans. The barge will shuttle between the vessel and the shore. But the sea is rough, and the wind is strong. Will the extraction be possible? Tension and uncertainty fill the air....