To confront Aldabra is to endure the island’s harsh conditions, but every effort is rewarded. A meeting with a tortoise, a sunset, a breathtaking landscape, the island gives back to those who care for it. But it never gives itself easily. It must be earned.

Wake-up call at five in the morning, surrounded by coconut crabs and ancient tortoises. The day ahead would be long. On Monday, October 13, Thibault, an engineer aboard Plastic Odyssey, and Simon Bernard, the expedition leader, set out to explore the southern coast of Grande Terre, one of Aldabra’s islands most exposed to the wind. Their mission: to map the most polluted sites in preparation for a massive cleanup operation planned for 2027.

The team began with a drone flight westward toward Takamaka, a point about two kilometers inland from camp. The first hour of walking went smoothly, but caution was still essential. “You have to stay alert at all times,” said Thibault. “One careless move can have serious consequences. The Takamaka camp is very basic, not maintained at all. The walls are made of sheet metal, and there are only two beds.”

To confront Aldabra is to endure the island’s harsh conditions, but every effort is rewarded. A meeting with a tortoise, a sunset, a breathtaking landscape, the island gives back to those who care for it. But it never gives itself easily. It must be earned. After lunch, the team set off again, this time heading toward Dune Jean-Louis (DJL), 18 kilometers away. “We each carried about 20 kilos on our backs,” said Simon. “It was exhausting because the terrain was so difficult. We walked over huge dunes, stepped across cracks in the karst rock. We probably should have roped up, because a single fall could have been fatal. Some sections had us balancing on the edge of cliffs above the sea. It wasn’t very high, maybe two meters, but if we had fallen, we’d never have been able to climb back up.”

Along the way, the team came across fishing buoys, a few plastic bottles, jerrycans, thousands of flip-flops, and tangled ropes. They also found large blocks of polystyrene eroded by the elements, resembling chunks of snow. Overall, the amount of waste was lower than expected. “There’s obviously plastic around, but much less than we anticipated,” said Thibault. “That’s encouraging when it comes to planning the big cleanup. But the problem will be extraction. In some sections, it’s nearly impossible to reach the shore by sea.”

The equation is complex. How do you remove 513 tons of plastic waste, scattered over sixty kilometers of harsh terrain? Simon Bernard has begun imagining possible solutions. Collectors could be equipped with wooden pack frames to carry the heaviest and bulkiest objects, such as jerrycans and ropes, to more accessible extraction points. Plastic buoys could be strung together and tied behind each cleaner, forming a kind of floating tail, a “wedding veil” trailing behind them. To move waste across the sharp karst, Simon suggested building bamboo slides, which are easy to find on the beaches. Linked together, these ramps could allow debris, pulled by a Zodiac, to glide across the rocky barrier and be retrieved at sea.

“As we walked along the coast, we logged GPS coordinates that will serve as reference points for extraction,” explained Thibault. “Some beaches could allow a platform to dock. Others, more sheltered from the wind, could be used as base camps. Each GPS point was filmed with a GoPro for logistical accuracy. Being on the ground helps us plan and visualize possible emergency scenarios too, like evacuation routes for injured people. Spending a few days on the atoll gives us an incredible amount of information that will be vital when it’s time to prepare for Aldabra’s big cleanup.”

By late afternoon, fatigue began to take its toll after twenty kilometers of walking with full packs. Suddenly, a drone appeared in the sky. It was Alexis, the professional diver working with UNESCO. The DJL camp was close now. A few more kilometers. The silhouettes of Maluha and François came into view. DJL was there, just ahead. What a relief.

Evening settled peacefully. Thibault, who had cut his leg on the karst rock, cleaned and disinfected the wound. Yes, Aldabra must be earned.

Author: Pierre Lepidi, Senior Reporter at Le Monde

Other articles

Day 1: “Aldabra, here we go!”

After spending a few hours at anchor off the Seychelles capital, the vessel set sail in the early afternoon. "Aldabra, here we go!" cheered Pierre-Louis, known to all as "Pilou", the second officer, as he sounded the ship’s horn. Under a cloudless sky, Plastic Odyssey first headed north along the coast of Mahé. Slowly, the island faded into the distance....

Day 2: “Aldabra is a paradise bristling against the invasion of man”

Aldabra has always inspired awe among those lucky enough to reach it. Yet its greatest defender was Commander Jacques-Yves Cousteau (1910–1997). Beyond revealing Aldabra’s coral beauty to the world, he made it his mission to protect it from the various forms of harm caused by humankind....

Day 3: Final preparations before landing on Aldabra

The vessel now moved to the rhythm of landing preparations, and nothing was left to chance. To protect biodiversity, the Seychelles Islands Foundation (SIF), the body responsible for regulating the atoll and issuing permits, requires that all equipment taken ashore on Picard Island be thoroughly cleaned of dust, sand, seeds, and soil....

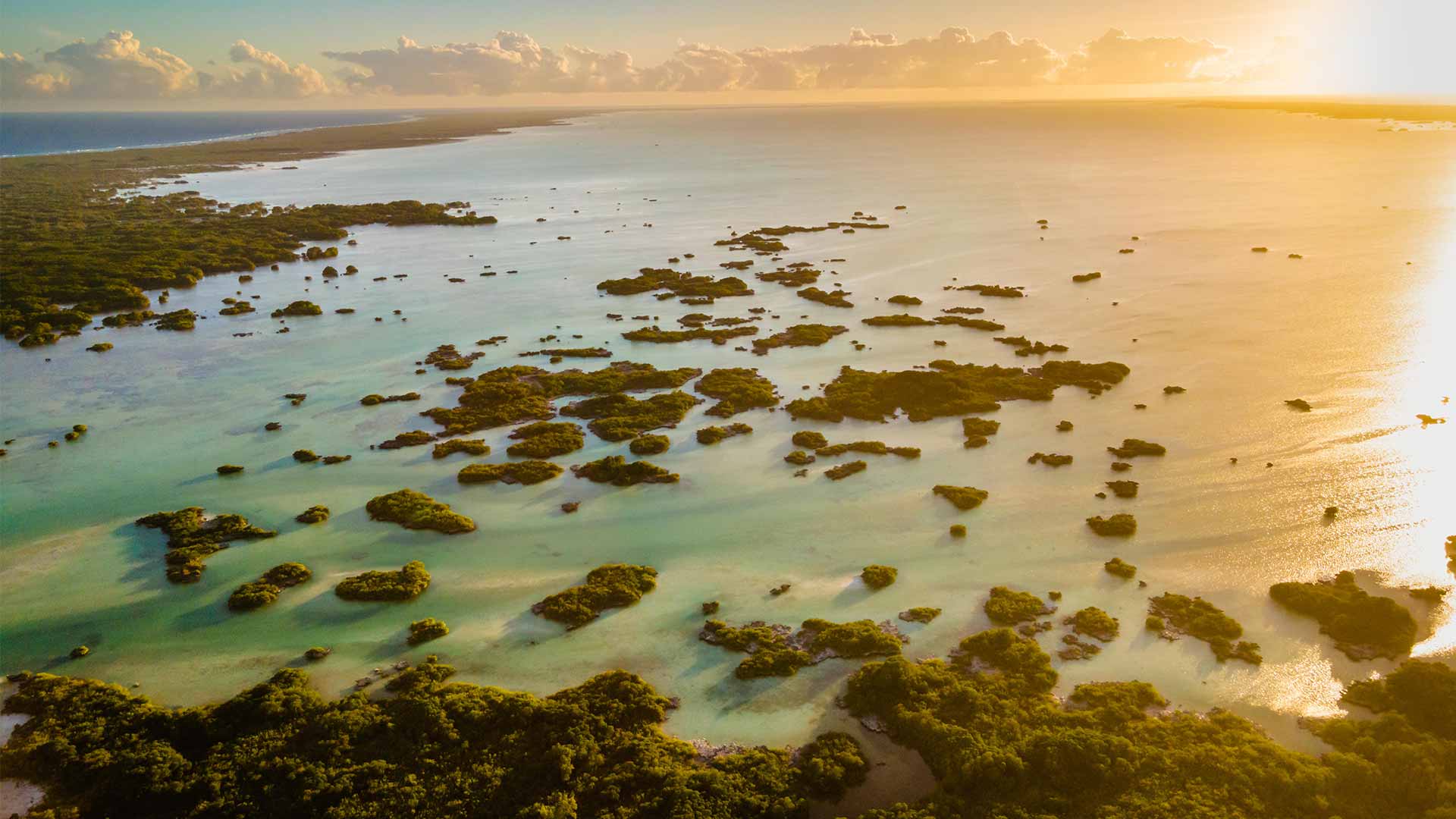

Day 4: Aldabra, seen from the sky

One of Plastic Odyssey’s missions is to map the areas where 513 tons of plastic waste were recorded during a scientific expedition in 2020. Driven by the trade winds, these piles have accumulated along the southern and eastern shores of the atoll, over roughly fifty kilometers. Some of these zones, as satellite images show, are extremely difficult to reach....

Day 5: Aldabra, the challenge of water

The heat was oppressive, almost suffocating. The first challenge was to get the seawater desalination unit running to rehydrate. "Water is life. The first priority in any survival situation is always access to water," explained Thibault, engineer aboard Plastic Odyssey. Since there are no natural sources on Aldabra, the scientific team relies exclusively on filtered rainwater for their daily needs....

Day 6: East of Aldabra, a lunar landscape swept by the trade winds

After waking, the Plastic Odyssey team decided to watch the sunrise from the top of the dune beside the DJL camp. Rising about twenty meters high, it is the atoll’s highest point. From up there, nature came alive in calm and color. Aldabra stretched out in every direction. The first light of day glowed orange and gold, as if the island were trying to seduce us....

Day 7: Aldabra does not give itself away, It must be earned

To confront Aldabra is to endure the island’s harsh conditions, but every effort is rewarded. A meeting with a tortoise, a sunset, a breathtaking landscape, the island gives back to those who care for it. But it never gives itself easily. It must be earned....

Day 8: Aldabra asks to be protected

Night had fallen. A dozen tortoises surrounded us. Almost naively, I asked Francis, the island's manager, what message Aldabra might want to send to the world. "It would be a cry from the heart," he said. "I am unique. Protect me."...

Day 9: Life Among Aldabra’s Giant Tortoises

The sea turtle reaches the plastic debris: she skirts a fishing buoy, crushes a plastic bottle. Farther on, a tire, a few jerrycans, some sandals. Watching her struggle through this apocalyptic landscape feels unreal, deeply moving....

Day 10: Mission accomplished for Plastic Odyssey on Aldabra

The Plastic Odyssey is expected off Dune Jean-Louis at 10 a.m. to test the extraction of half a ton of plastic waste using a floating platform made of jerrycans. The barge will shuttle between the vessel and the shore. But the sea is rough, and the wind is strong. Will the extraction be possible? Tension and uncertainty fill the air....