The heat was oppressive, almost suffocating. The first challenge was to get the seawater desalination unit running to rehydrate. “Water is life. The first priority in any survival situation is always access to water,” explained Thibault, engineer aboard Plastic Odyssey. Since there are no natural sources on Aldabra, the scientific team relies exclusively on filtered rainwater for their daily needs. Every drop consumed outside the base must therefore be carried or desalinated.

A scent of adventure filled the air as the first members of Plastic Odyssey set foot on Aldabra. A light breeze swept along the coast, and the sand sparkled like something out of a postcard or a computer wallpaper. It took several trips back and forth to unload all the expedition equipment. Each item had been carefully inspected aboard the vessel by scientists from the island’s base to ensure that no one brought seeds or soil onto the atoll, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1982. The rest of the gear, tents, sleeping bags, and supplies, had gone through the same process the day before in a room at the scientific station dedicated to this essential biosecurity procedure.

Around ten in the morning, all the equipment was loaded onto three boats, including the Frigate, a motor launch once seized by the Seychellois government from Somali pirates. The loading took place about a hundred meters from the scientific base, near a wide “pass.” To reach it, the team followed a path shaded by trees, passing several idyllic coves. The same trail was used by a dozen giant tortoises and led to a small beach where the wind blew hard and the current was fierce.

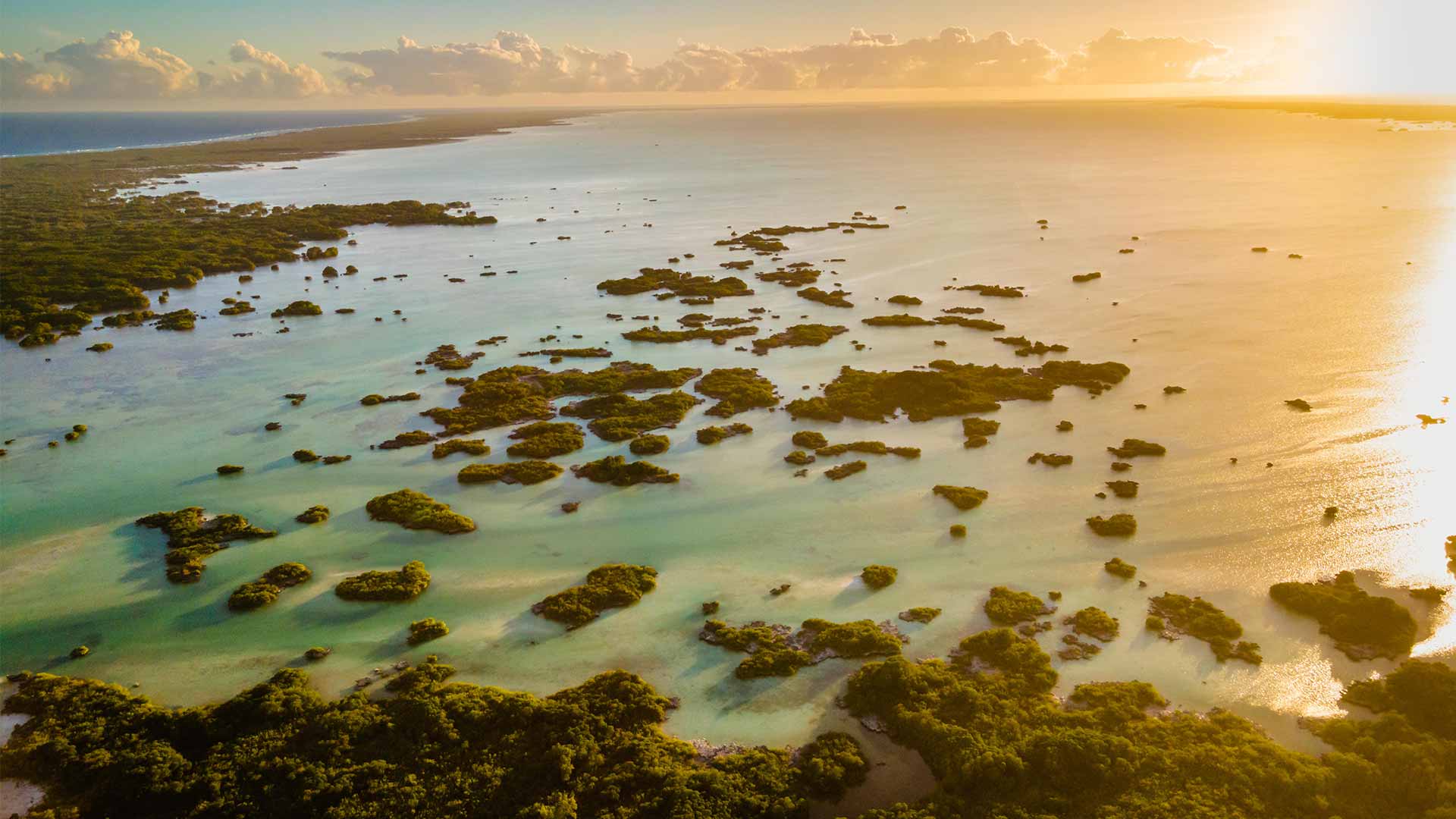

In just five minutes, the supplies were loaded once again, and the Plastic Odyssey team climbed aboard. Course set for the southeast. Excitement was at its peak. At the center of the atoll, the lagoon stretched endlessly, nearly 34 kilometers long, encircled by four islands: Picard (home to the scientific base), Malabar, Polymnie, and Grande Terre, where most of the plastic waste is concentrated, since it lies to the south and east.

That Saturday, October 11, the emerald lagoon was far from calm. The waves were high, and the team was drenched each time the boat picked up speed. Yet the spectacle was unforgettable: in the shallow water swam dozens of sea turtles, their strong flippers propelling them gracefully ahead as if guiding the way.

After about an hour of a rough crossing, we entered a narrow channel carved through the heart of the mangrove, a true labyrinth of water and roots. The heat was stifling, and an almost eerie silence surrounded us. “We won’t be able to go any farther,” said Evanio, one of the employees of the Seychelles Islands Foundation (SIF), the organization that manages Aldabra. “We’ll have to push the boat for about fifty meters to reach the landing point.” Our feet sank halfway into the muddy clay, slippery as soap. We had to take care not to trip over the tangled mangrove roots. But the hardest part was still ahead.

Karst is a geological formation shaped by water over millennia, carving out hundreds of cavities of varying depth. Fragile and eroded by wind and sea, the rock is as sharp as a razor blade. It was on this treacherous terrain that we finally landed on Grande Terre. The disembarkation took more than an hour and required several trips back and forth between the boat and the camp, known as Dune Jean-Louis (DJL), located about twenty minutes’ walk inland.

The heat was oppressive, almost suffocating. The first challenge was to get the seawater desalination unit running to rehydrate. “Water is life. The first priority in any survival situation is always access to water,” explained Thibault, engineer aboard Plastic Odyssey. Since there are no natural sources on Aldabra, the scientific team relies exclusively on filtered rainwater for their daily needs. Every drop consumed outside the base must therefore be carried or desalinated.

Thibault and Simon Bernard, expedition leader, set up the solar panel to power the osmosis unit designed to turn seawater into drinking water. The device, weighing twelve kilos, began to pump, but after twenty minutes, not a single drop came out of the hose. A fitting, likely damaged during transport, was removed, cleaned, and reattached, but to no avail. “We’ll try again tomorrow,” sighed Simon. “It’s important that we get it working, because we’ll soon be heading to the Dune de Mess camp, where there’s no water stored in the tanks. Otherwise, we’d have to carry fifteen liters per person, which is impossible given all the equipment we’re already hauling.”

While waiting to fix the desalination system, the SIF staff kindly agreed to share their water with the Plastic Odyssey team. What a relief. Their throats were parched after the lagoon crossing and the long effort of carrying equipment to the camp.

The “Dune Jean-Louis camp”, nicknamed “DJL”, is a wooden shack open to the elements, built about thirty meters from the waves. It has two rooms. The first serves as a kitchen and dining area, a place for conversation and planning strategies for future waste removal operations. The second holds six bunk beds, their mattresses coated in dust and sand. The expedition’s gear is stored in one corner. Ropes hang from the ceiling to dry clothes, usually soaked in sweat. Off to the left, connected to the sleeping area, is the bathroom, where showers are taken with a bucket. There are no toilets. Needs are met on the beach, facing the sea. A small plastic shovel, like the ones children use to build sandcastles, serves to cover the waste.

At DJL, you must enjoy sharing space with animals. A dozen tortoises have taken up residence right outside the door, feeding on food scraps and sipping dishwater to cool off. At night, countless crabs emerge, some weighing four or five kilos. And then there are the rats. They dart across the shack as soon as night falls, their shadows flickering along the wooden walls.

After a short rest inside the camp, the team organized its first waste collection. Later in the afternoon, Thibault and Simon went snorkeling in front of the dune. “Visibility wasn’t great, but we were amazed by the size of the fish,” recalled Simon. “In very shallow water, I saw a huge trevally and crossed paths with the biggest triggerfish I’ve ever seen.” On land or underwater, Aldabra teems with life.

Author: Pierre Lepidi, Senior Reporter at Le Monde

Other articles

Day 1: “Aldabra, here we go!”

After spending a few hours at anchor off the Seychelles capital, the vessel set sail in the early afternoon. "Aldabra, here we go!" cheered Pierre-Louis, known to all as "Pilou", the second officer, as he sounded the ship’s horn. Under a cloudless sky, Plastic Odyssey first headed north along the coast of Mahé. Slowly, the island faded into the distance....

Day 2: “Aldabra is a paradise bristling against the invasion of man”

Aldabra has always inspired awe among those lucky enough to reach it. Yet its greatest defender was Commander Jacques-Yves Cousteau (1910–1997). Beyond revealing Aldabra’s coral beauty to the world, he made it his mission to protect it from the various forms of harm caused by humankind....

Day 3: Final preparations before landing on Aldabra

The vessel now moved to the rhythm of landing preparations, and nothing was left to chance. To protect biodiversity, the Seychelles Islands Foundation (SIF), the body responsible for regulating the atoll and issuing permits, requires that all equipment taken ashore on Picard Island be thoroughly cleaned of dust, sand, seeds, and soil....

Day 4: Aldabra, seen from the sky

One of Plastic Odyssey’s missions is to map the areas where 513 tons of plastic waste were recorded during a scientific expedition in 2020. Driven by the trade winds, these piles have accumulated along the southern and eastern shores of the atoll, over roughly fifty kilometers. Some of these zones, as satellite images show, are extremely difficult to reach....

Day 5: Aldabra, the challenge of water

The heat was oppressive, almost suffocating. The first challenge was to get the seawater desalination unit running to rehydrate. "Water is life. The first priority in any survival situation is always access to water," explained Thibault, engineer aboard Plastic Odyssey. Since there are no natural sources on Aldabra, the scientific team relies exclusively on filtered rainwater for their daily needs....

Day 6: East of Aldabra, a lunar landscape swept by the trade winds

After waking, the Plastic Odyssey team decided to watch the sunrise from the top of the dune beside the DJL camp. Rising about twenty meters high, it is the atoll’s highest point. From up there, nature came alive in calm and color. Aldabra stretched out in every direction. The first light of day glowed orange and gold, as if the island were trying to seduce us....

Day 7: Aldabra does not give itself away, It must be earned

To confront Aldabra is to endure the island’s harsh conditions, but every effort is rewarded. A meeting with a tortoise, a sunset, a breathtaking landscape, the island gives back to those who care for it. But it never gives itself easily. It must be earned....

Day 8: Aldabra asks to be protected

Night had fallen. A dozen tortoises surrounded us. Almost naively, I asked Francis, the island's manager, what message Aldabra might want to send to the world. "It would be a cry from the heart," he said. "I am unique. Protect me."...

Day 9: Life Among Aldabra’s Giant Tortoises

The sea turtle reaches the plastic debris: she skirts a fishing buoy, crushes a plastic bottle. Farther on, a tire, a few jerrycans, some sandals. Watching her struggle through this apocalyptic landscape feels unreal, deeply moving....

Day 10: Mission accomplished for Plastic Odyssey on Aldabra

The Plastic Odyssey is expected off Dune Jean-Louis at 10 a.m. to test the extraction of half a ton of plastic waste using a floating platform made of jerrycans. The barge will shuttle between the vessel and the shore. But the sea is rough, and the wind is strong. Will the extraction be possible? Tension and uncertainty fill the air....